The Hinks Shipyard - By Alison Boyle

HINKS’ SHIPYARD, BIDEFORD, NORTH DEVON

In 1967, shipwright Alan Hinks (pictured, leaning forward) opened a large covered shipyard in Watertown, on the coast of North Devon, building wooden launches and fishing boats.

|

In 1968, the yard was commissioned to build a replica of the Hudson Bay Company’s Nonsuch, a 17th century, two-masted ketch.

In 1971, they were commissioned to build our very own Golden Hinde, and the keel was laid that year.

Alan’s daughter Alison has shared her photo album and memories with us below. All images and copy reproduced by kind permission of Alison Boyle.

You can listen to our podcast with Alison here.

|

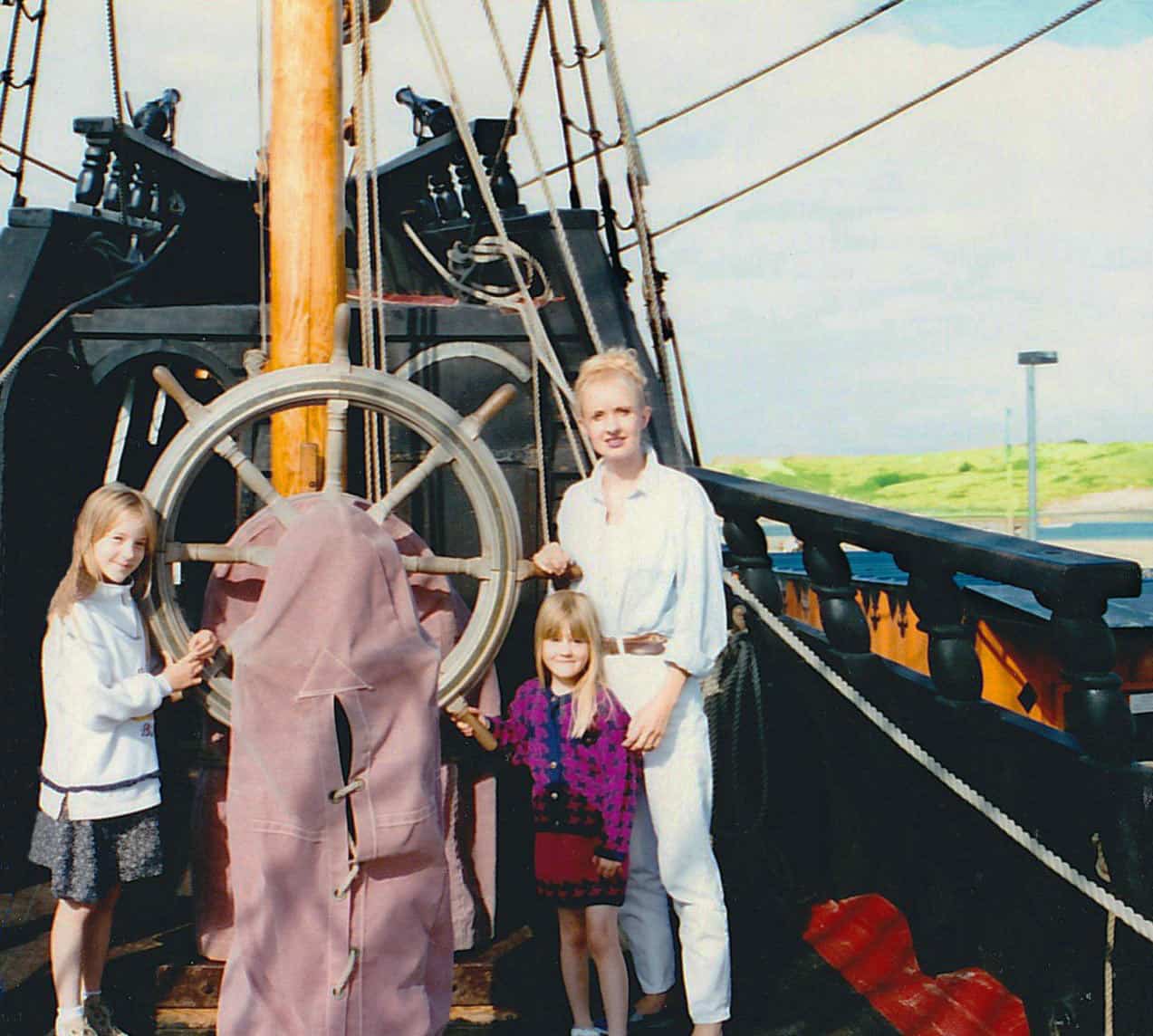

This is the only photo of me on the Hinde (I was always the one taking the photos!), taken on the half-deck when she visited Padstow in 1995.

I’m with my two eldest children, Corinne and Natasha.

|

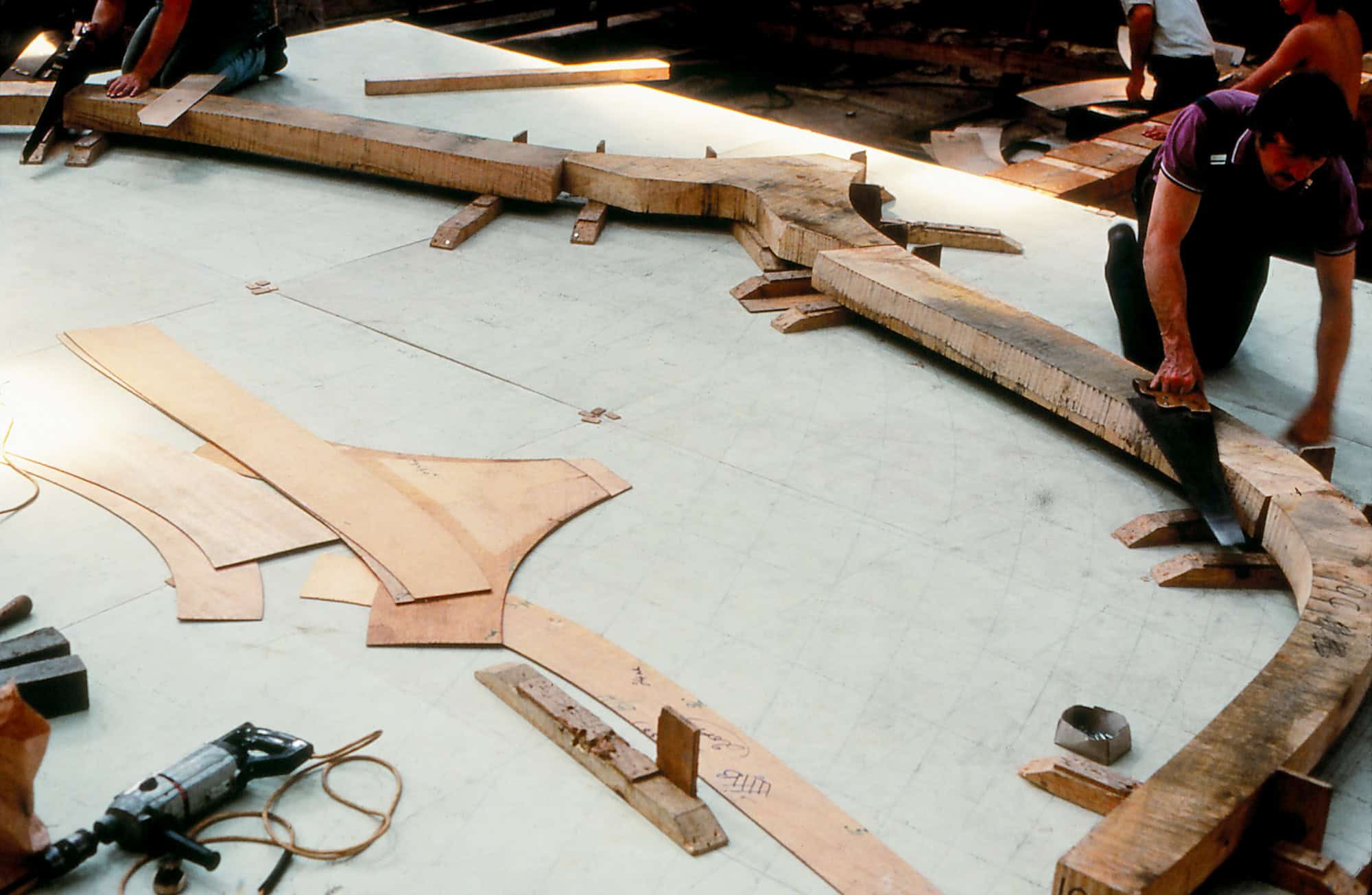

I was really pleased with this image because it shows the curvature of the timbers which will go into the hull. The first - and main - timber is the keel. On top of the keel lies a second timber. This adds strength to the keel but has also got regular grooves cut out, into which the frames are fitted. This timber was called the hog.

The frames are formed of five sections. The first is called ‘the floor’ and is shaped like a wide, soft ‘V’. On each side of the V are fitted sections called futtocks - a term I used to love using when giving talks. The futtocks are the rounded sections of the frame , one on each side of the floor. The final pieces are the top timbers.

Once the plans had been received they would be taken up to the mold loft, which was on the second floor of the yard. The plans would be drawn out in real size on large plywood boards and then carried downstairs to be laid on the keel. Patterns would be made of the frames and then used for cutting out the five sections of the frames. (I can always remember the foreman saying to my father that they had only just had enough timber needed, to which my father kindly smiled and replied that he had obviously got it right!) The photograph shows the sections of frames being stacked up in preparation for assembly.

|

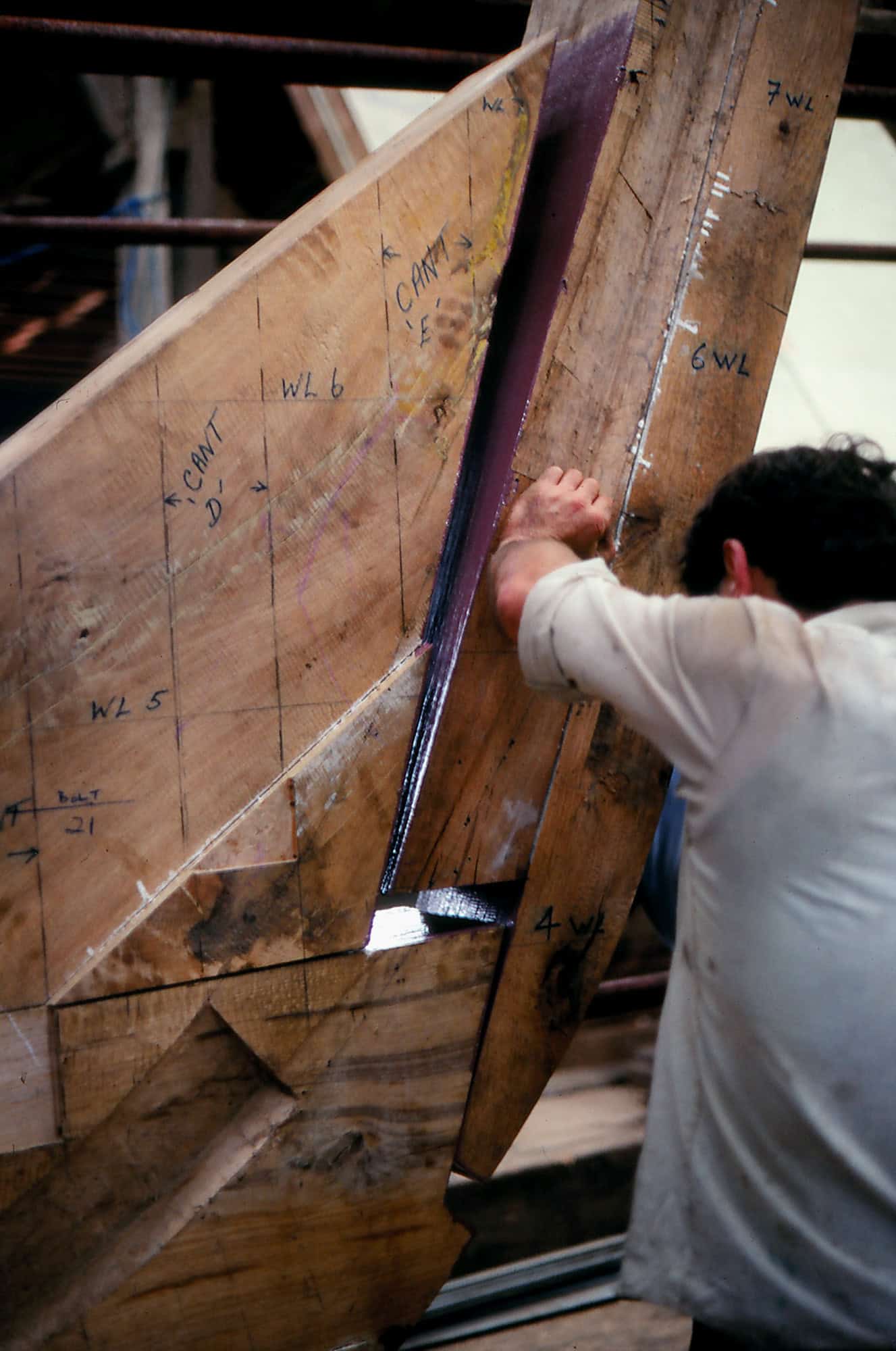

This shows the frames on the scree board. You can see quite clearly the ‘V’-shaped floor piece, and then there is a straighter section of timber, attached to which there is the final component. However, it is on this section that I can see the curve that forms the futtock. This correlates to the flow of the bilge.

I can remember going to the Maritime Museum in London with my father and being shown a contemporary drawing of shipbuilders in a medieval shipyard drawing out plans in a similar fashion.

|

In this picture, you can see the shipwright carving out the rabbet. The rabbet refers to a groove set in a main timber, such as the stem or stern or keel, where another piece of timber forms a joint.

|

Here is the stem being set in place. This would have involved a section of the yard's roof being removed and the section being lifted in by a crane, which would have been sited outside the yard. There would have been a lot of shouting as members of the yard would have had to raise their voices to be heard by the crane operative. The crane would have been sited on a lorry so it was quite involved to make sure that everyone could work together.

|

This is the task of caulking the plank with oakum to create a watertight seal.

This reminds me of the various smells in the yard. Iroko would have a sweeter almost fruity smell whilst oak, which is so often thought of as the heart of our shipbuilding, had a smell of sweaty feet - which was disappointing.

And then we have the oakum, which had a heavy rope smell. Rather than drive the oakum in between the planks in a straight line, there was always a slight loop between each section which enabled a doubling up of the oakum.

|

This is a close-up of a hand adze, a tool that dates back to the stone age, and would be used across the world for anything from art carvings to the earliest canoes - verifying the fact that little has changed in the method of wooden boat building!

My father always used to say that the curve of the head, combined with the weight, would make it easy to produce the curve that was necessary in timbers such as the knees.

|

This photograph shows a trunnel – also known as a tree nail, trenail or trennel - being driven in, in order to seal the gap where a nail had been driven through a plank. This is to ensure that it is fastened tightly to the frame of the hull, and effectively making it watertight.

|

Here is the hull of the Hinde alongside the quay at the dock of Appledore Shipyard. My father was very fortunate to have access to this. It was a combination of the friendship between himself and Joe Ball - who was the Managing Director of Appledore Shipyard.

The raising of the mast was very emotional because it turned the Hinde from merely a hull into a ship! It was a massive venture ensuring that the base of the mast fitted directly into the section which had been prepared and this was governed by the control of the shipwrights on board. These men are clearly shown in the photo.

Once the masts and sails were in place the Hinde could be taken for trials. I would dearly have loved to go on the trials but my father had said that I couldn't because, apart from my age, it was considered unlucky to have a woman on board. Ironic considering that all boats and ships are termed 'she'!

|

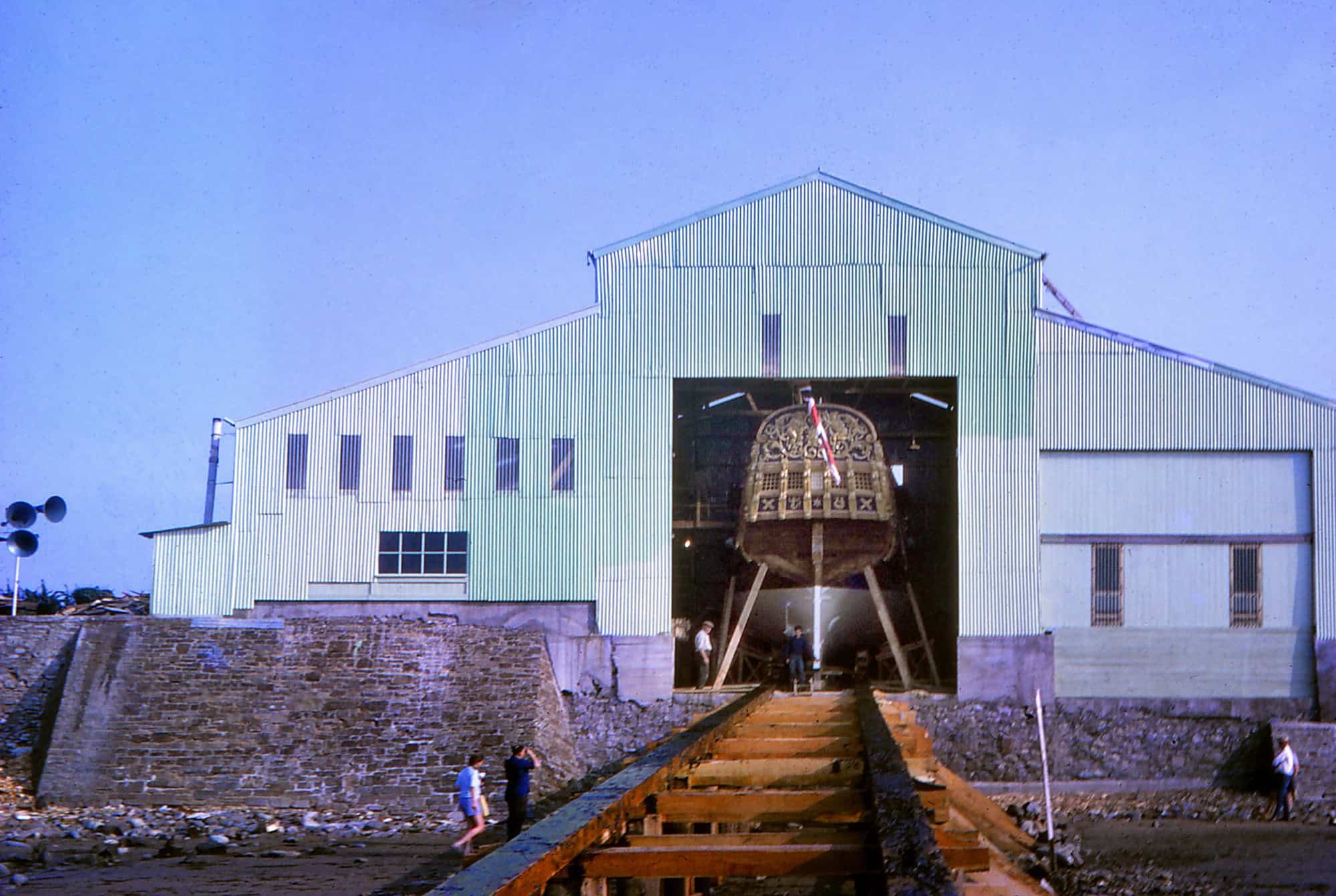

This a shot of the Nonsuch ready for launching, using the same process as was used for the Hinde. You can see that it’s being held in place by the regular shores on either side. When my father gave the order, these were simultaneously knocked out until the last two shores were left. These were known as the dog shores.

When the Hinde was launched, there had been a tremendous amount of interest, with visitors ranging from Angela Rippon, of the local television company to John Mills, the famous actor.

There is a film of the Hinde’s launch available on YouTube, which I am sure you have seen, and which brings out the tears...

|